Kevin Goebel

Tobacco Control 1994; 3: 65-67

[I wrote this commentary in 1994 for Tobacco Control, a British journal published by BMJ Journals, the publishing division of the British Medical Association. It’s been cited in other journal articles 39 times since it was first published more than 25 years ago, most recently in September of 2020. British spelling and punctuation from the original publication has been retained.]

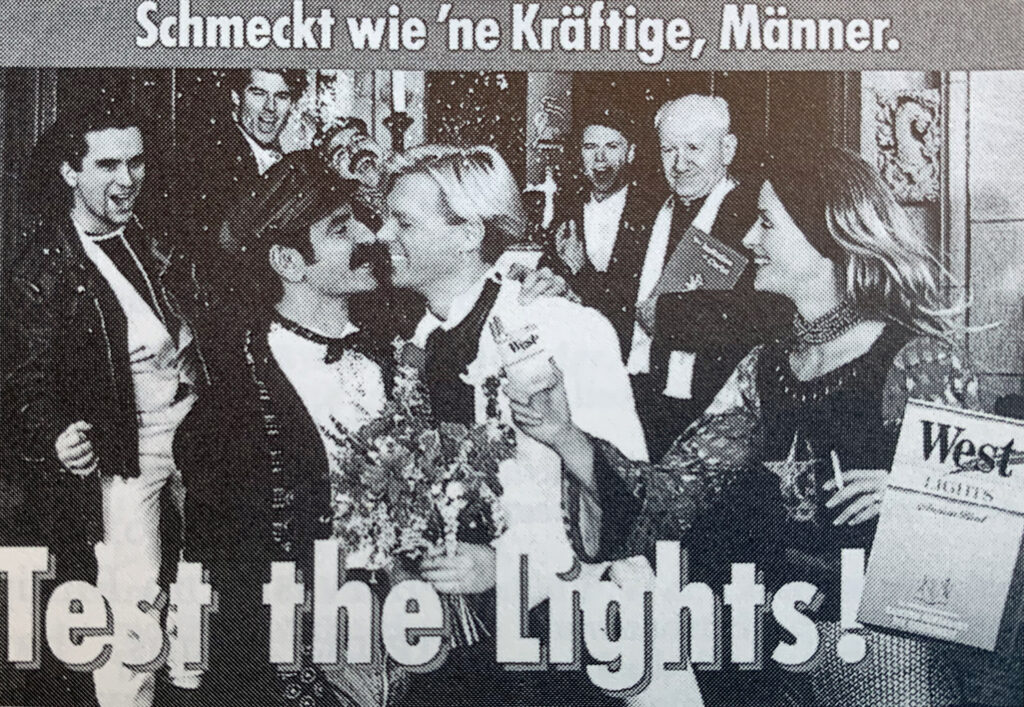

A new ad by the German cigarette company, Reemstma, for its New West brand, shows a gay marriage, with two men embracing, sur- rounded by friends (figure 1). The ad includes an English caption, “Test the Lights!” along with the German “Schmeckt wie ’ne Kraftige, Manner” – characterised by Advertising Age as “trumpet[ing] the brand’s strong taste, positioning it as the choice of fearless individuals “[1]

By standards in the US, the ad may be the most blatant targeting of lesbian and gay smokers, but it is far from the first attempt. Alcohol companies, including many owned by tobacco manufacturers, have courted lesbian and gay consumers for decades, but only in the past few years have tobacco companies followed suit.

An ideal market?

Lesbians and gays may be an ideal market for tobacco companies. They represent a fiercely loyal and virtually untapped market. This is an attention-starved community and very brand-loyal”, said Jeff Vitale, president of Overlooked Opinions, a market research company specialising in the gay and lesbian community.[2] “Ninety-four per cent say they will buy products that advertise [in gay magazines] or support the gay community.”

In addition to their loyalty and reportedly high discretionary incomes, lesbians and gays smoke at extremely high rates. Various studies have found conflicting data on smoking behaviour among gay men[3]: 46% of gay men were smokers in a 1982 study[4]; 41.8% in a 1984 study[5]; 44.3% in an unpublished 1990 survey (Gay and lesbian smoking and health survey, Santa Barbara Gay & Lesbian Re- source Center, Santa Barbara, California) ; and 37.3% in an unpublished 1991 study (San Francisco lesbian, gay and bisexual substance abuse needs assessment, EMT Associates, Sacramento, California). The latter study also found that about 25% of lesbian respondents smoked. These studies consistently found substantially higher smoking rates among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals than among heterosexuals.

The high smoking rates do not surprise most lesbian and gay health professionals. The pressures that result in teenage smoking – self-esteem issues and the need for peer acceptance, the need for rebellion and liberation, the development of style and individuality – are compounded for lesbians, bisexuals, and gay men struggling with their sexuality.[6] The bar culture, in part responsible for an alcoholism rate three times higher among lesbians and gays than that among the rest of the population,[7] was cited by 32% of lesbian and gay smokers as a factor in their nicotine addiction (Gay and lesbian smoking and health survey, Santa Barbara Gay & Lesbian Resource Center, Santa Barbara, California).

It’s not surprising, therefore, that tobacco companies would consider lesbians and gays to be a perfect market niche. It’s even less surprising that Philip Morris would lead the way; the company began noticing the lesbian and gay community in 1990 after a 1990-91 boycott by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) (over Philip Morris’ support of Senator Jesse Helms) resulted in increased tobacco industry contributions to AIDS organisations.[8]

Philip Morris aggressively targets lesbians and gays

In 1992 the Wall Street Journal reported Philip Morris’ plan to market its new Benson & Hedges Kings brand in Genre – a fashion and lifestyles magazine for gay men – and other gay magazines.[9] The plan was immediately criticised by lesbian and gay health professionals. “This is a community already ravaged by addiction””, said Hal Offen, president of the Coalition of Lavender-Americans on Smoking and Health (CLASH), in a press release sent Out the same day.[10] “We don’t need the Marlboro Man to help pull the trigger.” CLASH is an organisation of lesbian, gay, and bisexual tobacco control professionals volunteering their services to help their community.

Don Tuthill, publisher of Genre, defended accepting the ads. “It’s people, not products, that cause problems”, he insisted.[9] “We all have a choice. We can choose to smoke of not to smoke. We can’t be everybody’s keeper.”

But Offen disagrees. “We expect the tobacco industry to push their product,” he said,[11] “but it’s particularly aggravating when they find willing collaborators within our community who take no responsibility for their actions.”

The ad eventually appeared in Genre, but did not run in subsequent issues – perhaps a product of CLASH’s “Special Queens” counter-campaign, perhaps a result of Philip Morris’ fears of controversy.

Philip Morris isn’t about to ignore such a lucrative market. Like many companies marketing to lesbians and gays, Philip Morris may now be seeking a more subtle approach in order to avoid alienating more conservative consumers. Although the Benson & Hedges Special Kings ads no longer run in Genre, the ads still appear in Esquire and GQ (magazines with a high level of gay readers). Lesbians, too, are being targeted subtly.

The themes of independence and liberation, so pervasive in Philip Morris’ advertising for Virginia Slims, have always appealed to lesbians and gays who view accepting one’s sexual orientation as a liberating process of “coming out”. A new series of Virginia Slims ads appears to be specifically, but covertly, focusing on lesbians.

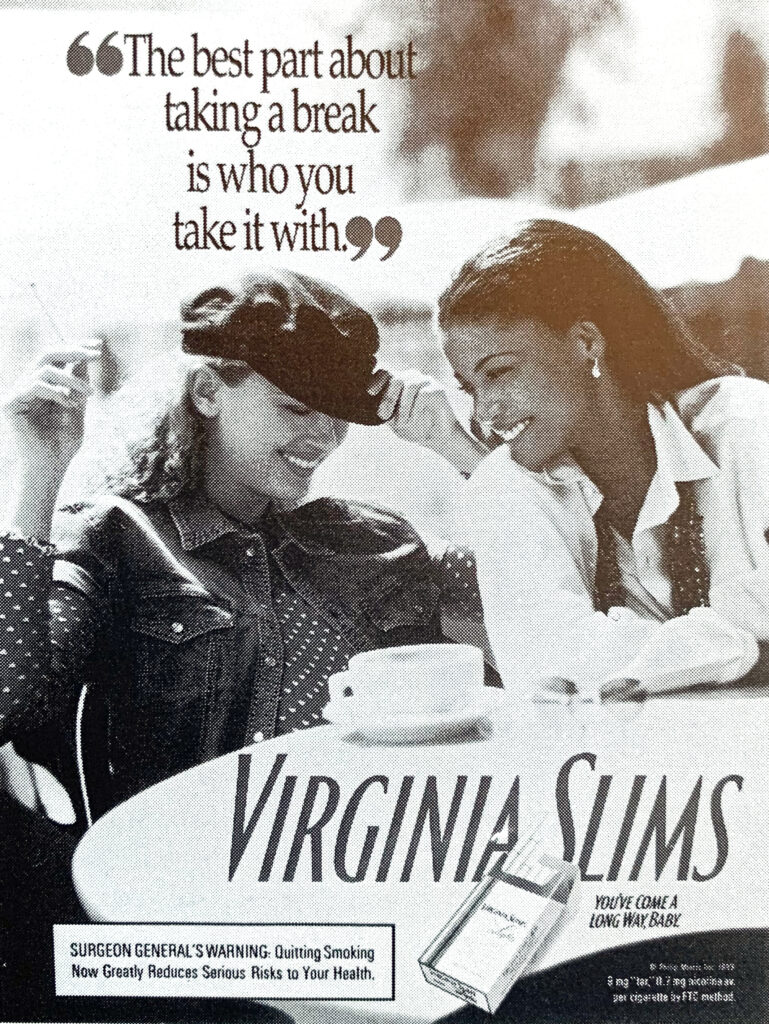

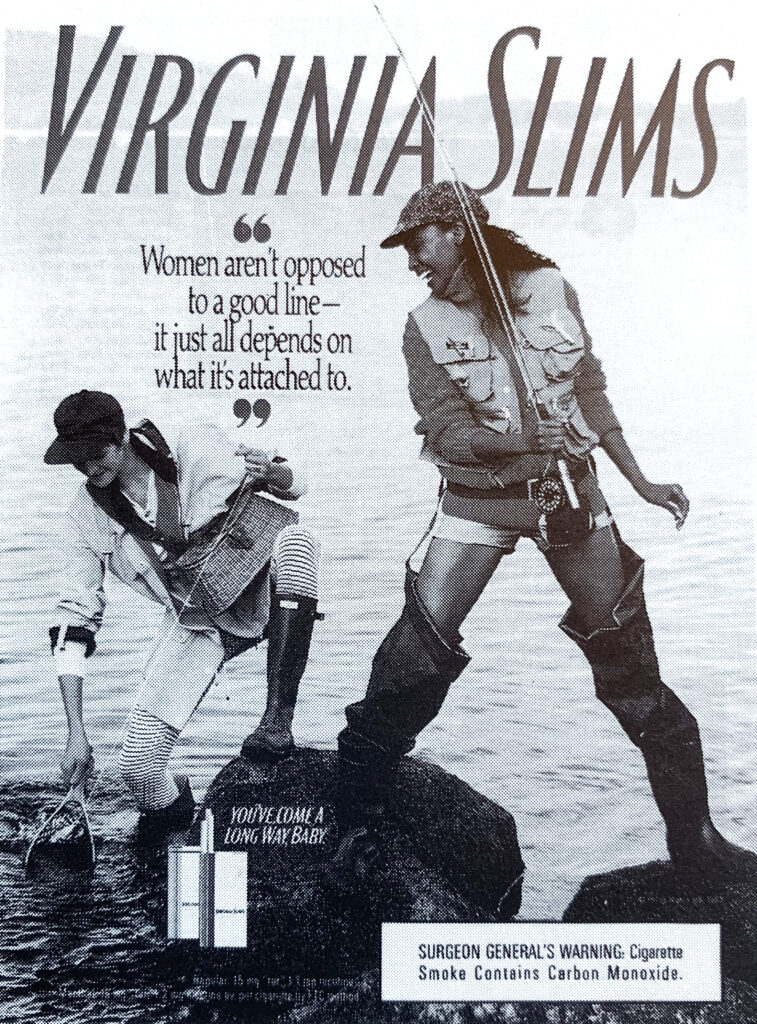

A few years ago, Virginia Slims began experimenting with androgynous models, some draped over motorcycles. Newer ads are even more direct, although in a manner that would be missed by most heterosexual women. One recent ad (figure 2) features two women laughing over coffee beneath the caption, “The best part about taking a break is who you take it with” – innocent enough by itself, but more revealing in light of companion ads running about the same time. “Women aren’t opposed to a good line – it just all depends on what it’s attached to”” proclaims another Virginia Slims ad showing two women fishing, one netting a fish caught on the other woman’s fishing line (figure 3).

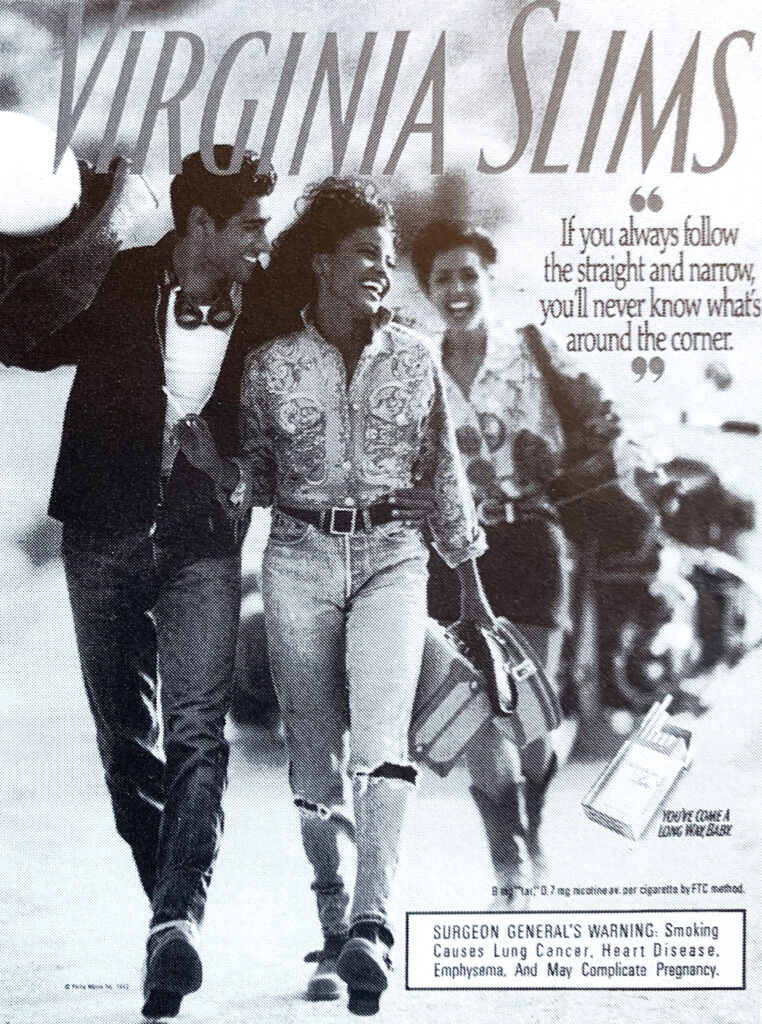

The most blatant ad helps tie the campaign together for “attention starved” lesbian readers looking for recognition of their community. The ad (figure 4) shows a heterosexual couple walking together, with the woman smiling over her shoulder at another approaching woman. The caption reads, “If you always follow the straight and narrow, you’ll never know what’s around the corner.”

The ads are vague enough to avoid offending conservative readers, but contain enough of a between-the-lines message to catch the attention of lesbian readers.

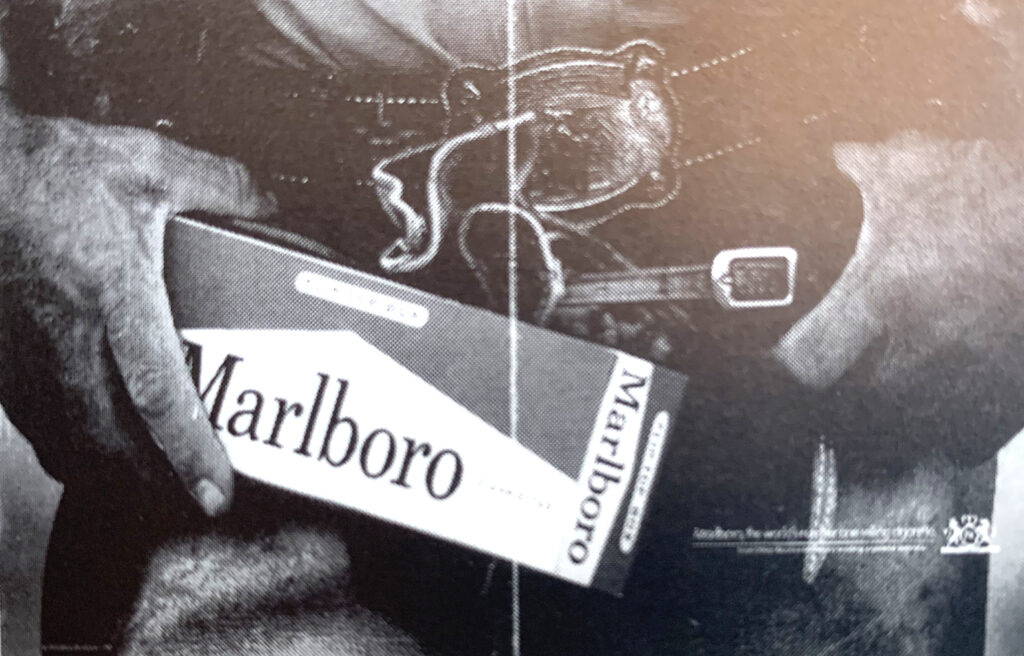

If Philip Morris can’t capture the gay market with Benson & Hedges and Virginia Slims, perhaps its flagship brand, Marlboro, can help. Already the most popular brand among both the general population and gay men, according to Overlooked Opinions,[9] Marlboro’s rugged, masculine image has always appealed to certain gay men. One ad may be the most obvious, however. A recent billboard in San Francisco featured only a denim-clad male crotch with a carton of Marlboro posed at a suggestive angle (figure 5). The billboard appeared between two gay bars in the Mission District.

Not to be left out, American Brands’ Montclair cigarettes have run ads showing what appear to be “aging, effeminate homosexual[s]”[2] since 1991 (see Tobacco Control 1993; 2: 158).

We have arrived – or have we?

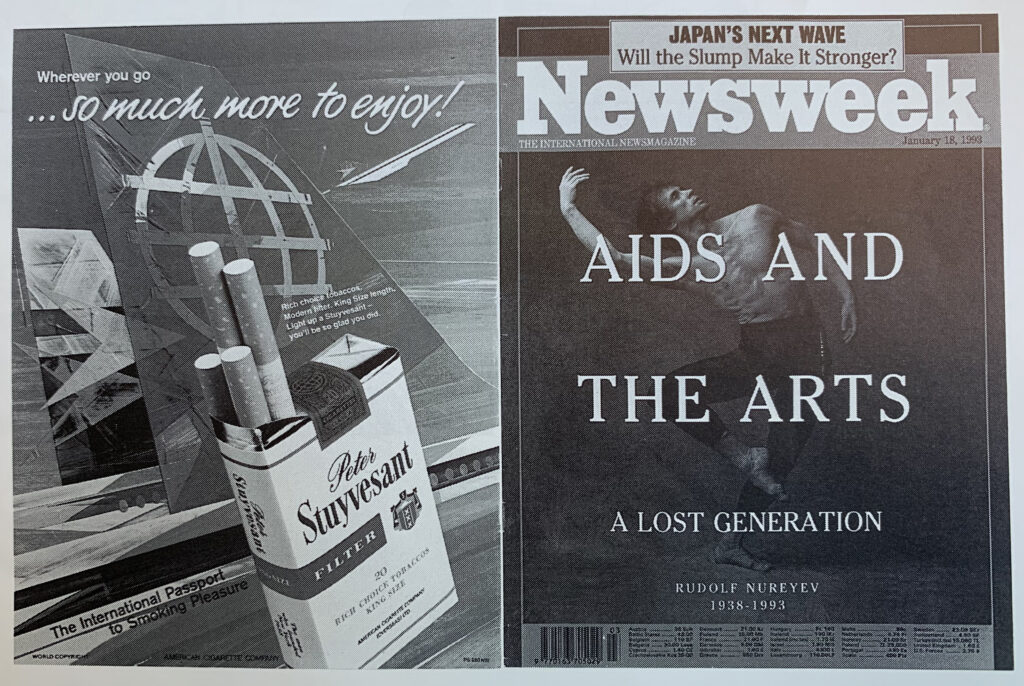

The tobacco companies’ interest in the lesbian and gay community has been obvious for a decade now. They courted gay voters in 1983 when they attempted to repeal a workplace smoking control ordinance in San Francisco.[12] Surveys for smokers have appeared in “Direct Male”, a postcard packet sent to mailing lists of gay men.[11] With advertising now ranging from the subtle (Virginia Slims), to the bizarre (Montclair), to the direct (Benson & Hedges Special Kings in Genre), and now to the blunt (New West), funding for lesbian and gay community groups may soon follow. This funding may well result in silence from both the gay press and gay community groups about tobacco epidemic. Lesbian and gay health advocates, like advocates in other communities, can look forward to fighting community groups’ addiction to tobacco money along with the routine fight against nicotine addiction.

[1] Global gallery. Advertising Age. 2S October I993: 40.

[2] Hidges M. Still taboo on Madison Avenue. Detroit News, 7 July 1991: 1D.

[3] Arday DR, Edlin BR, Giovino GA, Nelson DE. Smoking HIV infection, and gay men in the United Sates. Tobacco Control 1993; 2: 156-8.

[4] Burns DN, Kramer A, Yellin F, et al. Cigarette smoking: a modifier of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type Infection? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1991; 4: 76-83.

[5] Royce RA, Winkelstein W. HIV infection, cigarette smoking and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts: preliminary counts from the San Francisco Men’s Health Study. AIDS 1990; 4: 327-33.

[6] Goebel KC. Tobacco use among lesbian /gay youth. Presentation at the 1993 annual meeting of the American Public Health Association (Session 3034), 24-28 October 1993, San Francisco, California.

[7] Diamond-Friedman CA. A multivariant model of alcoholism specific to lesbian-gay populations. Alcohol Treat Q 1990; 7(2): 111-2.

[8] Gilden D. Philip Morris settlement sparks bitter dispute. Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), 6 June 1991.

[9] Lipman J, Philip Morris to push brand in gay media. Wall Street J, 13 August 1992.

[10] Coalition of Lavender-Americans on Smoking and Health. Philip Morris targeting cigarettes to gays (press release) San Francisco, California: CLASH, 13 August 1992

[11] Coalition of Lavender-Americans on Smoking and Health. Philip Morris targeting cigarettes to gays (CLASH Dispatch). San Francisco, California: CLASH, Winter 1992.

[12] Hanauer P. Proposition P: Anatomy of an ordinance. NY State J Med 1985; 85: 369-74.